Paralympic Games 2024 in Paris: Between a progressive vision and unfulfilled expectations

With 4,463 athletes from 170 countries competing in 549 events in 22 sports, the Summer Paralympic Games have become one of the largest sporting events in the world. The stadiums were packed, with 2.5 million tickets sold, almost reaching the record numbers of London 2012. Paris 2024 was a great victory for the visibility of disabled sports in society. And yet some of the high expectations were not met.

It was the first time that a member of the fairplay initiative went to the Paralympic Games. The impressions gathered cannot be compared to past Games. The report also does not claim to be complete or scientifically sound. Rather, it aims to discuss some highlights and lowlights of the human rights and sustainability aspects on site.

The motto for Paris 2024 was “Games wide open” (“Ouvrons grand les Jeux”). The slogan was intended to show that these games would be more inclusive, open and equal. The organizers had also taken up the issues of human rights and sustainability.

Since the direct Vienna-Paris train was not running for a few months due to construction work at the time of my trip, and a train journey would therefore have involved three changes and enormous amounts of time and money, I took the plane to Paris with a heavy heart.

Immediately after my arrival in Paris on Thursday, September 5, 2024, I made my way by train and metro to the “House of Friends”, which was organized jointly – but in separate areas – by the Austrian (Austria House) and the German Paralympic Committee (German House Paralympics). Already in the metro, I noticed the many advertising posters that included athletes in an inclusive way while recycling, and thus actively encouraged waste separation at this major event. Para-athletes or even disabled dancers were also strongly present on other advertising posters.

What also became immediately apparent, however, were the distances that fans in Paris had to travel – even though all the venues were accessible by public transport – and how few metro stations had (working) elevators.

Accessibility for fans?

Despite an investment plan of 1.5 billion euros for accessibility, NGOs such as APF France handicap criticized the slow implementation of measures and conversions.

In the run-up to the Games, the enormous investments in accessibility were repeatedly emphasized. In particular, the competition venues and the Paralympic Village were said to be well prepared for the para-athletes. According to many reports and interviews, it would be no problem for people in wheelchairs or with walking impairments to access the sports fields and halls. In practice, however, this proved to be a challenge: steep stairs, a lack of elevators – the historic metro is rarely barrier-free and often cannot be converted to be so.

With wheelchair-accessible shuttle buses and taxis, it was obviously possible for the para-athletes to avoid the city's obstacle course. Unfortunately, the same could not be said for the fans. The shuttle buses or taxis were only available to fans traveling to Paris at their own expense. And how environmentally friendly this increased use of cars was is also questionable.

Andrew Parsons, President of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC), also praised the city's efforts to make transportation accessible, but also pointed out the frustration felt by many people with regard to some parts of the public transportation system, particularly the century-old subway system, where 93% of stations were or are not or only partially accessible for wheelchair users.

Sustainability under the microscope: progress and blind spots

Unfortunately, when I finally arrived at the “House of Friends”, a rather sobering realization regarding ecological sustainability prevailed. Free plastic merchandise was available for free at the entrance and in the rooms themselves. At the bar, when I asked for a glass of water, I was kindly informed that I could get free water in a plastic bottle from the various fridges. At the huge buffet with dozens of starters, main courses and desserts, a chef proudly emphasized that the pumpkin for the soup and the fish had been “transported to Paris specially from Austria”.

As much as the Paris 2024 organizing committee has thought about plastic consumption and much more, it had little influence on the Paralympic committees of the individual countries, and it can be roughly calculated how much waste, including large amounts of disposable plastic, was generated every day by more than 150 competing nations.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the organizing committee for Paris 2024 has set itself ambitious sustainability goals and, in retrospect, has achieved them: In December 2024, it was announced that the carbon footprint of the Olympic and Paralympic Games could be estimated at 1.59 million teqCO2, a 54.6% reduction compared to the average of London 2012 and Rio 2016.

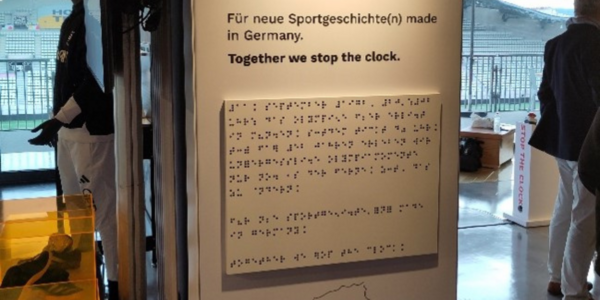

In terms of social sustainability, the “House of Friends” provided some positive examples, from the presentation of (young) athletes, the translation of information into Braille, to the display of clear rules of fair play and respect.

On Friday, September 6th, and Saturday, September 7th, I watched the judo and athletics competitions. There was a great atmosphere everywhere. Volunteers wearing vests with the Paris 2024 branding were standing at almost every station, at the entrances and exits, and on the way to the sports facilities, supporting fans and guests with any needs they might have. It is unlikely that these volunteers will also be on hand to assist people with additional needs after the Games.

With so much good cheer in the air, it was easy to forget how much plastic merchandise and how many flights are behind such a mega sporting event – no matter how extensive the sustainability strategies are. The eviction of homeless people or the enormous increase in AI surveillance in the wake of the games seemed less present in those moments.

Since inclusion is not just about people with disabilities, but also about other marginalized groups, I tried to have a holistic view of the events. Among other things, I immediately noticed that there were no binary security checks at the judo competitions at the Champ-de-Mars Arena; at the athletics competitions at the Stade de France, however, I was assigned to a female security guard. In none of the sports venues I visited were there any signs indicating gender-inclusive toilets. By comparison, the standards set for the UEFA EURO 2024 in June in Germany set completely different standards with gender-neutral toilets and entrances.

Green Event?

In terms of environmental sustainability, it was particularly noticeable in the Champ-de-Mars Arena how clearly the efforts in this regard were communicated. There were signs and directions to water refill points, vegetarian and vegan food options, waste separation, reusable energy and materials, and even bicycle services.

In the stadiums themselves, drinks were only sold in reusable cups, and efforts were also made to reduce the use of plastic for food. However, the example of the Stade de France quickly showed that the food stands around the stadium could not or did not want to make use of this. And the fact that Coca Cola, one of the biggest plastic polluters in the world and a company that even reduced its environmental goals for 2024, was a sponsor of the Paralympic Games made all the signs or efforts to promote reusable cups in stadiums seem rather irrelevant.

Rethinking inclusion? The Paralympics as a stage for diversity and fair play

In terms of accessibility – i.e. social sustainability – the competitions themselves offered the opportunity to follow an audio description through the Paris 2024 app, in addition to various explanatory videos shown directly before the events. Great importance was also attached to subtitles and sign language.

In terms of gender equality – Paris 2024 prided itself on the fact that, for the first time, there were as many male athletes as female athletes taking part – the imbalance among the moderators, referees and coaches was striking.

On Sunday, September 8, the games continued with two matches – including the final – of the women's wheelchair basketball team. In the Bercy Arena, too, waste separation played a central role; here, too, drinks were served in reusable cups (although the contents were transferred from plastic bottles).

The display of fair play was very striking for a newbie like me: the players helped each other up after almost every fall or foul – regardless of which team they were on. During the breaks, there were dance performances by standing dancers. There would certainly have been more room for inclusivity here, for example, by also including dancers in wheelchairs as part of the performance.

Apart from the competitions we attended, we also followed the 2024 Paralympic Games in the media, of course. One piece of news that particularly pleased us was that Zakia Khudadadi secured the first medal for the Refugee Paralympic Team by winning bronze in the women's para-taekwondo (K44 to 47 kg). Three days later, Guillaume Junior Atangana, who won a medal at the Olympic or Paralympic Games, followed suit by also winning bronze in the men's 400-meter run (T11). Hadi Hassanzada, who lives as a refugee in Austria, was accepted into the IPC Refugee Team and was able to compete in Paris.

Italian Valentina Petrillo also made history by becoming the first openly transgender athlete to compete in the Paralympics in Paris.

The 50-year-old Petrillo qualified for the semi-finals of the women's 400 and 200 meter races in the T12 category for visually impaired athletes. Although she unfortunately did not qualify for the final, she achieved her personal best time of 57.58 seconds.

From lack of recognition to normalization

The branding of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games has also attracted positive attention.

Although the focus of the past Paralympic Games has been on empowering athletes and spectators, the event's previous tone can be described as misguided at best and patronizing at worst. Historically, brand, communications and marketing have been the three main issues here. From a brand perspective, for example, the Paralympic Games have often been trivialized and treated as an inferior version of the Olympic Games.

For example, the British television channel Channel 4 portrayed Paralympians as “superhuman” in its 2012 and 2016 advertising campaigns, thus suggesting, so to speak, that there is something heroic about being disabled. The team behind Channel 4's Paris 2024 advertising has definitely corrected the mistakes of the past and is now positioning Paralympians as top athletes and no longer as people who “are doing well considering...” But there is still work to be done to change public perception.

The Paris 2024 organizing committee has also played a large role in trying to change the narrative. In designing the identity for Paris 2024, the critical role of branding was recognized and a unified approach was developed that brings both events together under a common visual identity – a first in the history of the modern Games.

While previous Games have created separate Paralympic mascots for the disabled, Paris 2024 linked both mascots and used a shared symbol (the Paralympic mascot was slightly modified with an artificial leg). The disabled mascot was the first to sell out.

In addition, the pictograms were gender-neutral for the first time, and the sports were represented by a single, unified pictogram wherever possible.

According to research by adam&eveDDB, many people tend to use the term “competition” when talking about the Olympics, but “participation” when talking about the Paralympics. It is seemingly insignificant semantic things like this that create a gap between the two events. In this regard, for example, the social media strategy tried to break new ground. Among other things, the IPC encouraged Paralympic athletes to normalize their experiences. For example, social media templates were provided that allowed some athletes to jokingly announce just days before the opening ceremony in Paris that they would no longer “participate” in the Games. Shortly afterwards, however, they clarified that they would instead “compete”.

This was a subtle but effective way of encouraging Paralympians to indirectly refer to paternalistic stereotypes about disability.

Overall, the 2024 Paralympic Games in Paris offered many advances, particularly in the portrayal of para-athletes as elite athletes and in the accessibility of the competition venues. The ecological sustainability measures, especially in terms of (new) construction, operation and travel, were ambitious and were officially achieved. However, it remains unclear to what extent the countless side events, for example, were included in the data for the carbon footprint.

Paris 2024 was certainly a step forward and can be considered a success story within the Olympic and Paralympic movement in many ways. But the road to a truly inclusive – and, above all, sustainable – major sporting event is and remains a challenge!

Photos: Hanna Stepanik